Grade: (9.7/10)

On his way to becoming the “father of the atomic bomb,” J. Robert Oppenheimer is forced to navigate dilemma after dilemma.

Plot (48/50)

Nolan utilizes his favored non-linear storytelling, but there were still three distinct acts to this film. The first act focuses on Oppenheimer’s origins and influences on his way to becoming director of the Manhattan Project. During the second act, the focus shifts onto the successful creation of the bomb at Los Alamos despite many hardships. The final act addresses important moral and political repercussions to Oppenheimer and others as a result of the bomb’s creation.

“Theory Can Only Take You So Far”

Oppenheimer’s journey into quantum physics starts in Europe, where he studies under various leading physicists. Once he’s developed a good understanding of the subject, he returns to the US, where quantum physics has yet to take off. Oppenheimer takes up a position in UC Berkeley as a professor. At first, there is little interest in the subject, but with time, the subject gains footing. And as the subject gains footing, so does Oppenheimer’s standing in the community.

During this time, Oppenheimer’s social life is quite active as well. Through his brother, he’s introduced to prominent members of the Communist party. While not a communist himself, Oppenheimer was interested in various ideologies, and as a result, he has no trouble slotting in. He even begins a relationship with Jean Tatlock, a staunch member of the party. Unfortunately, Oppenheimer’s association with known communists puts him on the FBI’s radar. This, coupled with his support of unions and anti-fascist fighters in the Spanish Civil War, proves troublesome later on.

Now back to the physics of it all. Shortly before WWII broke out, news of German physicists making a groundbreaking discovery reached the US. These physicists had managed to induce nuclear fission using uranium. Lawrence, a colleague of Oppenheimer’s, quickly confirms this discovery in his lab despite Oppenheimer’s calculations claiming the reaction was impossible. Then, in the midst of exciting scientific discoveries, the Nazis start WWII.

The Manhattan Project

The war brought this discovery to the fore due to its potential to create an atomic bomb. Initially, Oppenheimer was excluded from the war effort due to his aforementioned links to the communist party. At some point, Lawrence explicitly tells him that he needs to tone down his radical sympathizing if he’s to ever be involved in the project. Oppenheimer is smart enough to recognize that Lawrence is right, so he adapts accordingly. This earns him a meeting with General Groves.

Groves is not particularly fond of Oppenheimer. He recognizes that Oppenheimer’s affiliations are a concern, but he also recognizes his brilliance. It helped that Oppenheimer had broken up with Jean Tatlock in favor of a marriage to “Kitty,” who herself was a former member of the Communist party. In any case, Oppenheimer sells Groves on the idea of building a central lab in Los Alamos, New Mexico. They end up building a town to house the scientists and their families in an effort to mitigate the risk of information leakage.

Meanwhile, Oppenheimer and Groves get to work recruiting the top scientists from around the nation. Some are brought to Los Alamos while others were stationed at labs across the nation. This perpetuated Groves’ edict of “compartmentalization.” All the while, Oppenheimer’s security clearance was still being held up. He eventually manages to brute force his way into getting cleared. Put simply, he was needed, so his past was once again overlooked. I say overlooked because he would never truly shake his past. But that’s for later in the story. For now, he becomes the director of the Manhattan Project.

Los Alamos

Most of the second act takes place at Los Alamos as Oppenheimer leads his team of brilliant, idiosyncratic scientists towards the creation of an atomic bomb. Oppenheimer has to contend with clashing egos and external pressure to deliver. He does a commendable job, for the most part. And in the moments where he starts to falter, Kitty is there to set him straight. One such moment comes when he gets news of Jean’s suicide. He blames himself for not being there for her when she needed him, but Kitty sternly reminds him of his responsibilities. He is exactly where he is needed most.

Amidst the tragedies, fallouts, and politicking, Oppenheimer and co. make considerable progress. As they approach the testing of the bomb, the intensity starts to turn up. What follows is a suspenseful sequence where everything seems to be going wrong. The night before the test is to be conducted, a storm breaks out. As a result, there was serious doubt in the detonators’ functionality. Proceeding with the test would risk a faulty detonation that would scatter years worth of plutonium, but delaying it would rob President Truman of significant leverage at the Potsdam Conference. Oppenheimer has to make a decision.

He chooses to trust in his colleagues and in his intuition that the storm would settle. In both cases, he was right. “Trinity,” as they called it, was a spectacular, devastating success. They had done it. Groves quickly reports the news to the president. Some had hoped that Truman would share news of the bomb’s existence with the Soviet Union, but he ultimately chooses only to strongly suggest that it exists. In any case, they had done their part. It was now up to the government to decide how the bomb was to be used.

Put on Trial

The third and final act serves as a judgement of Oppenheimer. The bomb was used in Japan twice. and as news of its utter devastation came to the fore, Oppenheimer is gripped with a sense of guilt. He feels there is blood on his hands; he even says as much to Truman, who is thoroughly unimpressed. Oppenheimer concludes that expressing his guilt would get him nowhere, so he embraces his status as “father of the atomic bomb.” This allows him to maintain his standing within the scientific community whilst also playing to his newfound fame. Taking this position maximized his influence.

He uses this influence to try and sway both politicians and the general public against building an extensive nuclear arsenal. Specifically, he was against the development of Hydrogen bombs. This put him at odds with Lewis Strauss, who was chair of the Atomic Energy Commission at the time. Strauss had previously appointed Oppenheimer director of Institute for Advanced Study, but their relationship soured as they clashed on key issues. Eventually, Strauss makes a concerted effort to have Oppenheimer’s security clearance revoked.

When Oppenheimer appeals the decision, he is subjected to a security hearing that goes so far as to accuse him of being a Soviet spy. The whole thing was rigged by Strauss, so the appeal is rejected. Oppenheimer loses his security clearance, but he is cleared of treason. Strauss’ actions come to light during the Senate’s confirmation hearings into his appointment into President Eisenhower’s Cabinet. He is ultimately denied in humiliating fashion. Neither he nor Oppenheimer would continue their active roles in government. And while neither man was ever put on trial, their actions were most certainly judged.

Overall Thoughts

This was a brilliant film. Nolan’s non-linear storytelling is always engaging, but with a topic this serious and complex, anchoring the story to a somewhat linear flow was imperative. Nolan strikes a balance that keeps the viewer engaged even throughout the somewhat slower start. With that said, once the film gets going, it doesn’t look back. The Trinity test is, in itself, a spectacle. The buildup is grippingly suspenseful. Delaying the sound of the explosion is a masterstroke that forces the viewer to take in the gravity of the moment. Muffling the sound of the audience during Oppenheimer’s speech is another bit of brilliance that conveys the horror of the achievement.

The story is then allowed to breathe for a bit before the intensity starts to crank up again. The parallels between Strauss and Oppenheimer’s unofficial trials make for incredible drama. The “trials” themselves serve as highly effective tools that translate Oppenheimer’s internal judgement of himself as well as that of the nation’s. He was a brilliant man, no doubt, but he was flawed. Showing his flaws will hopefully prevent viewers from glorifying him.

And of course, there are some big “grey area” moments. They are, of course, designed that way to get the viewer thinking. I mentioned the delayed sound of the bomb. There was the matter of the glove during Jean’s “suicide.” Was that simply Oppenheimer blaming himself for her death, or was she murdered by the FBI? Nolan was, no doubt, aware of that theory, thus the ambiguity. Finally, that final scene between Einstein and Oppenheimer leaves us with a lasting impression that should resonate now more than ever.

Character Development (14/15)

The film centers around its titular character, and as a result, just about all character development goes through him. The complexity of Oppenheimer’s character is explored through the various challenges and accomplishments throughout his life. Other important characters are not given as much time to develop, but they are very well-defined. As a result, Oppenheimer’s complexity is enhanced through his interactions with the likes of Kitty, Groves, Jean, and Einstein.

Young and Impulsive

As a student, Oppenheimer’s academia was completed in Europe. During this time, he was often anxious and homesick. He struggled with lab work and did not enjoy practical science. Instead, he was far more interested in theoretical physics. Oppenheimer becomes so frustrated with his situation that he once tries to poison his professor. However, once he is allowed to study the subject of his interest, his situation improves dramatically.

This was an effective introduction that highlighted Oppenheimer’s talents and flaws. He clearly possesses tremendous intellect, but he lacks the maturity needed to navigate a social setting. As a result, he is unable to advance in a manner befitting of someone with his potential. Fundamentally, he lacked direction. It just goes to show that even the most capable of us are stifled when we can not map a way forwards. Only when Oppenheimer is set on the right path that he begins recognizing his potential.

Brash, Insufferable Genius

Oppenheimer returned to the US as a pioneer in quantum mechanics. He cultivated interest in the subject mostly during his time as professor at UC Berkeley. He maintained good relationships with his students and colleagues, especially Ernest O. Lawrence. The two complimented eachother as Lawrence was a capable experimental physicist who would go on to win a Nobel prize himself. His stock was rising in the scientific community, but his personal life was not as smooth.

Due to his brash nature, some found him pretentious and, at times, insufferable. He was generally tolerated, but his perceived arrogance would get him in trouble later on in his life. What could not be tolerated was his proclivity for liberal causes. Oppenheimer openly supported unionizing academia, the anti-fascism resistance in Spain, and the communist cause. Oppenheimer’s affiliation with prominent members of the communist party would ultimately prove his undoing. He never joined the party, but he was sympathetic to the cause just as he was sympathetic to other causes.

At face value, one might consider this naivety on Oppenheimer’s part, but that wasn’t the case. He knew that his interests were considered radical by some, but he was never one to limit himself based on what others thought. He unapologetically pursued the ideas and subjects that interested him. With that said, he does develop a somewhat naive hope for American acceptance of communism despite seeing plenty of evidence that would strongly suggest such a tolerance would never materialize.

Complicated Feelings

Around this time, Oppenheimer develops a relationship with Jean Tatlock, a prominent member of the Communist party. Jean was intellectually capable, but she was emotionally broken and chronically depressed. Oppenheimer cared for her deeply, even after she broke off their relationship. Shortly after, he meets his future wife, Katherine “Kitty” Puening. Kitty’s fiery, emotionally driven personality is a match for Oppenheimer, and the two wed after Kitty gets pregnant. Jean is devastated by the news, but Oppenheimer consoles her by promising to always answer her call. That promise would be put to the test years later.

For now, let’s shift back to his marriage to Kitty. That two weren’t ready to be parents when they had their first child. Kitty struggled with alcoholism and Oppenheimer was too obsessed with his work to focus on raising a child. They had to call on their friends to help them through the challenge of parenthood. With time, they were able to materialize as a family. Kitty would serve as Oppenheimer’s emotional support in several critical moments, one of which involved a certain ex.

Years after their breakup, while Oppenheimer was working on the Manhattan Project, Jeans calls. The two have an affair, but because of increased scrutiny into his relationships, Oppenheimer tells Jean that he can no longer answer her call. This would be the last time he saw her, as she would allegedly commit suicide a few months later. When he gets news of her death, Oppenheimer is devastated. He blames himself and feels a sense of guilt for not being there when she needed him. Ironically, it is Kitty who snaps him out of it. This would become a theme in their relationship.

Mutual Respect

After his marriage to Kitty, Oppenheimer’s he next major life event was his appointment as director of Los Alamos. The man who appointed him was General Groves. Groves was a stern military man who was in some cases the polar opposite to Oppenheimer and his theatrics. He was aware of Oppenheimer’s problematic association with know communists, and he was less than impressed with Oppenheimer’s moral standing and demeanor. Still, he had the professionalism to judge Oppenheimer based on his value with respect to the task at hand, so he ended up getting the job.

Groves and Oppenheimer got along rather well. In many cases, they complimented eachother. Their partnership was fruitful because they had an understanding of one another. Oppenheimer obviously kept his side of the bargain, but Groves did as well, and that should not be overlooked. Groves kept the dogs at bay far away and long enough for Oppenheimer to perform the miracle he was tasked with. Because the two trusted eachother, they rarely stepped on each other’s feet, and that’s the ultimate indicator of a successful partnership.

Groves’ background in engineering made him the perfect man for the job because he had an inherent understanding of how difficult it is to create something. Furthermore, Groves’ unwavering sense of dignity, honor, and loyalty was not reserved to any one institution. Instead, he always found a way to do justice by Oppenheimer without compromising his honest duty to serve his country. This was most evident in the way he handled himself at the “trial.” He spoke of Oppenheimer’s character glowingly and vouched for his loyalty, even if he did have to play into Robb’s hands in the end. Nonetheless, the respect was always there.

From Tormented Creator to Political Scapegoat

After Japan’s surrender due to the devastation of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Oppenheimer was revered as an American hero. However, he sure didn’t feel like it. He and others tried to justify the bomb’s creation, but the more detailed information came out about the desolation caused by the bombs, the more disillusioned he became. Oppenheimer felt a sense of guilt, as if he had set the world on a path to utter destruction. He even says as much to Einstein at the end of the film. His hopes for global cooperation were dashed when it became clear that the US would never consider the Soviets a true ally.

Oppenheimer tried to right his wrongs by using his position to influence foreign policy. He opposed the creation of a Hydrogen bomb because he felt it would push the Soviets to bolster their nuclear arsenal as well. This put him at odds with many important political figures, including Strauss. Unfortunately, Oppenheimer was fighting a losing battle. His argument was based on the assumption that the Soviets were several years behind, so when that was disproven, Oppenheimer’s credibility took a major hit. That was followed up with the gut punch that was confirmation of a Soviet spy at Los Alamos. Oppenheimer was devastated.

“Now I Am Become Death, Destroyer of Worlds”

That brings us to his “trial.” Oppenheimer had publicly humiliated Strauss on one occasion, and Strauss never forgot about it. As their views grew farther and farther apart, their relationship deteriorated. Strauss was an ambitious man who was now driven by a grudge, so when he saw an opportunity to get back at Oppenheimer, he took it. He orchestrated the sequence of events that saw Oppenheimer’s security clearance revoked even going so far as to set up a rigged, closed “trial” for his appeal. Strauss had Oppenheimer exactly when he wanted him, and he succeeded in bringing him down, but it came at a monumental cost.

Strauss’ overconfidence ultimately proved to be his undoing. He was reliant on the testimonies of scientists who disagreed with Oppenheimer, but they did not play into his hands. Instead, they (mostly) stood by their colleague. Dr. Hill took it one step further by calling Strauss out for his vicious agenda against Oppenheimer. That proclamation would lead to Strauss’ downfall, as it managed to sway enough votes away from Strauss’ confirmation to the Cabinet. He was humiliated once more, but this time, it was his own doing.

As for Oppenheimer, he saw the “trial” as a way to absolve himself of his sins. He didn’t fight back with the expected fervor, much to the frustration of Kitty. She most certainly did not have any reservations defending her husband, not that it mattered in the end. Several years later, Oppenheimer was recognized with the Enrico Fermi Award as a way to cement his legacy. Still, he would be haunted by his accomplishment for the remainder of his life.

Theme/Messages (5/5)

- “You know the truly vindictive, patient as saints…”

- “Genius is no guarantee of wisdom.”

- “Power stays in the shadows.”

- “Just remember, it won’t be for you. It will be for them.”

- “You can’t lift the stone without being ready for the snake that’s revealed.”

- “They won’t fear it until they understand it. And they won’t understand it until they use it.”

- No one is too big to fail.

- In hindsight, we know that weapons of mass destruction have served as deterrents. The creation of the atomic bomb ushered the world into an unprecedented era of global peace. These weapons will continue to perpetuate peace until they don’t. Meaning the cost of peace now is potentially the complete and utter destruction of our world should anyone ever decide to unleash a nuclear war. That’s the catch.

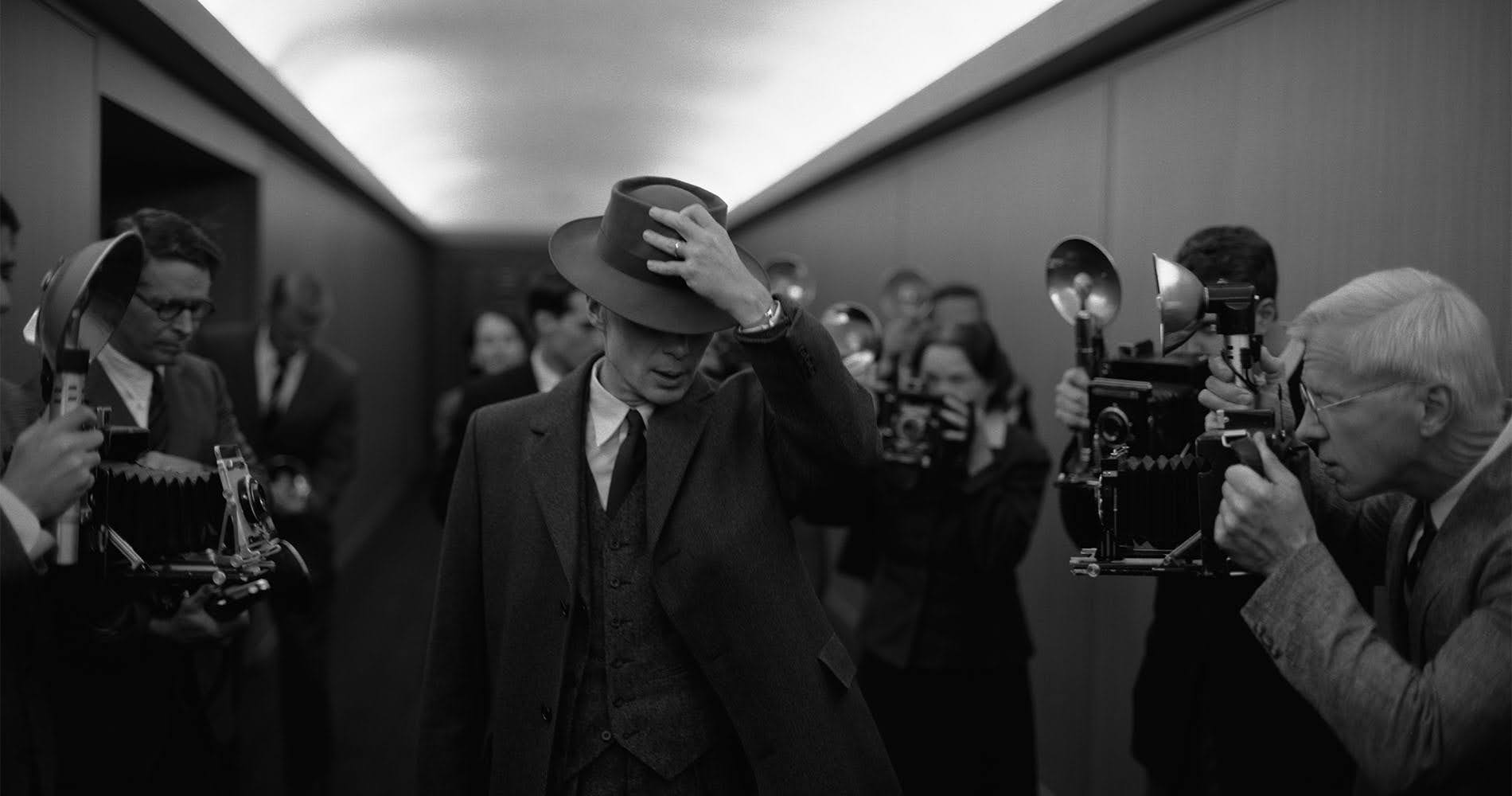

Acting (15/15)

Cillian Murphy (Oppenheimer) delivers a mesmerizing performance with an intentionality and intensity that does not falter for even a moment. It is, by all accounts, an Oscar-worthy performance for an actor that is finally getting the plaudits he deserves. Not only is he believable as the titular character, he embodies him. You could feel the inner turmoil of Oppenheimer through Murphy’s eyes and subtle mannerisms. With these types of movies, the depiction of the main character literally makes or breaks the movie. In this case, Murphy’s awe-inspiring performance not only makes the movie, it enhances it.

Good films require great performances from their main actors. Great films require great performances from the supporting cast. This was a great film. Robert Downey Jr. (Strauss) is fantastic as the bitter antagonist opposite Murphy. Matt Damon (Groves) does a tremendous job serving as a sort of anchor to Murphy’s character. Emily Blunt (Kitty) and Florence Pugh (Jean) make the best out of their more limited roles. All four have such amazing chemistry with Murphy that allows them to make an impression through their characters without ever taking the focus away from Murphy’s character.

But it goes even further than that. Rami Malek (Hill) delivers a picture-perfect performance with the 5 minutes he has on screen. Tom Conti (Einstein), Benny Safdie (Teller), Josh Hartnett (Lawrence), Gutaf Skarsgård (Bethe), Josh Peck (Bainbridge), David Dastmalchian (Borden), Gary Oldman (Truman), Casey Affleck (Pash), Kenneth Branagh (Bohr), Jason Clarke (Robb), Dane DeHaan (Nichols), David Krumholtz (Rabi), the list goes on and on. Every single actor delivers, no matter how limited their role. What a colossal achievement for all involved.

Cinematography (15/15)

This was a visually stunning film with an outstanding score to match. It’s definitely worth a watch in IMAX. Here are some highlights:

- The opening montage featuring a younger Oppenheimer went a long way towards setting the tone.

- During the montage, Oppenheimer can be seen watching raindrops in a puddle. This was a sort of foreshadowing to the explosions at the end of the film.

- Flashes of atomic matter would occasionally cut in almost as a way to give the viewer a brief look into Oppenheimer’s mind.

- The addition of a black glove in the scene where Jean drowns was an effective way to introduce the well-documented uncertainty over her death whilst also visualizing Oppenheimer’s feelings of guilt.

- The explosion itself was something to behold. Delaying the sound of the explosion was a brilliant twist.

- If you had to watch once scene out of the whole film, go watch the stomping scene in the gym.

- The final stretch of Oppenheimer’s questioning where the ambience starts to intensify around Oppenheimer as he comes under increasing pressure was another great sequence.

- Nolan’s use of black-and-white scenes to depict historically accurate events was another masterstroke.

- A close up of Oppenheimer’s blank expression after he tells Einstein that he believes they started a chain reaction that would destroy the world, followed by depictions of atomic bombs raining down on Earth, left a lasting impression.